Case in Point: Sun Pharma Ltd vs. DWD Pharma Ltd

Case in Point is a new series where we discuss case laws and explain certain basic concepts which may be useful to all practitioners and students alike.

The first part of this series focusses on the recent judgment of the Delhi High Court in Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd v. DWD Pharmaceuticals Ltd[1], wherein the Delhi High Court in an Order 39 Rule 4 application preferred by the Defendant, had imposed costs on the Plaintiff for suppression of material facts but at the same time confirmed the ad-interim ex-parte order of injunction granted to the Plaintiff. The judgment is succinctly put, merely 24 pages but provides an opportunity to revisit certain concepts.

Brief Facts:

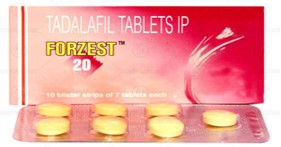

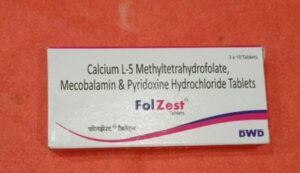

The Plaintiff claimed that the defendants mark ‘FOLZEST’ infringed its mark ‘FORZEST’. The Delhi High Court on 19.05.2022 had granted an ad-interim ex-parte order from infringing the Plaintiff’s mark. Thereafter the Defendant preferred an application under Order 39 Rule 4 read with Section 151 of the Civil Procedure Code ‘CPC’ for setting aside the order dated 19.05.2022. The primary ground raised by the Defendant was that the Plaintiff had obtained the ad-interim ex-parte by concealing certain material facts from the Court. The Defendant claimed that it had a family of registered marks with ‘ZEST’ forming part of them. That even when the Plaintiff’s predecessor in interest had applied for registration of its mark ‘FORZEST, the Defendants mark ‘FERIZEST’ was cited as a conflicting mark and a reply had been filed by the Plaintiff’s predecessor in interest.

The Plaintiff however claimed that it came to know of the Defendants mark only in May 2022 and had immediately filed an application opposing registration of the same.

Order 39 Rule 4; when and who can file an application?

Order 39 Rule 4 of the CPC states that an injunction may be ‘discharged, varied or set aside’ by the Court on an application made by any party dissatisfied with such order. Therefore, an injunction can be ‘discharged, varied or set aside’ only if a formal application is made by a party dissatisfied with the order. Though Order 39 Rule 4 uses words ‘any party dissatisfied with the order’, the Courts have interpreted the words to mean only those who are parties to the suit and that such an application cannot be maintained by 3rd parties[2]. Furthermore, the order of injunction must be varied not on statements made at the bar, but on cogent evidence adduced.

The 1st Proviso

Suppression of material facts to obtain an injunction is dealt with in the 1st proviso to Order 30 Rule 4. In order for the said proviso to apply, two conditions have to be met.

- A party must have made any false or misleading statement in relation to a material particular in the application for temporary injunction;

- and that the injunction was granted without giving notice to the other party.

Again, it isn’t any false or misleading statement but a material one. ‘Material facts’ are those primary or basic facts which must be pleaded by the party concerned in support of the cause of action or defence[3]. What is material is to be determined in accordance with the facts of each case, but it must be material and of such a nature that if surfaced on record may disentitle the suitor to get an injunction[4]. Despite finding that there has been suppression of material facts, the Court need not set aside or vary the injunction, if it considers that it is not necessary to do so in the interest of justice.

The 2nd Proviso

The 2nd proviso deals with situations where orders of injunction have already been issued to the other party. Such orders of injunction will not be ‘discharged, varied or set aside’ on an application of a party except when the same has been necessitated by a change in circumstance or the Court is satisfied that the order has caused undue hardship to the party.

Order 39 Rule 4 though commonly used by Defendants to set aside ad-interim ex-parte orders of injunction, is even available to Plaintiff’s who at one point may have obtained an interlocutory order of injunction but due to a subsequent development or change in circumstance, require the same to be varied[5].

Test of deceptive similarity and how is it different for medicinal products?

What weighed with the Court to ultimately not set aside the injunction, despite finding that there was suppression of material fact by the Plaintiff, was the deceptive similarity between both marks relating to medicinal products. The Plaintiff’s medicine ‘FORZEST’ is used for treating erectile dysfunction in men and that of the Defendant ‘FOLZEST’ is a multivitamin for pregnant women for lowering pre-term births.

This poses for our consideration another important concept as to what is deceptive similarity in trademarks and how is it different in respect of medicinal products?

Deceptive Similarity in Trademarks

Section 2(h) of the Trademarks Act, 1999 states that a mark shall be deceptively similar to another if is so nearly resembles the other mark as to be likely to deceive or cause confusion. The Trademark Act does not lay down any criteria on what is likely to deceive or cause confusion, so we must look towards precedent. In celebrated case of Pianotist Company Justice Parker has enunciated the test for determining deceptive similarity as under:

“You must consider the goods to which they are to be applied. You must consider the nature and kind of customer who would be likely to buy those goods. In fact, you must consider all the surrounding circumstances; and you must further consider what is likely to happen if each of those trademarks is used in a normal way as a trademark for the goods of the respective owners of the marks.”

Several Indian Courts have followed this, some of which can be found here, here and here.

The Supreme Court has in Amritdhara v. Satya Deo stated that for deceptive similarity you must ask two questions:

- who are the persons whom the resemblance must be likely to deceive or confuse, and;

- what rules of comparison are to be adopted in judging whether such resemblance exists.

In deciding the similarity between two marks, the question has to be approached from the point of view of a man of average intelligence and of imperfect recollection[6].

How is this test different for medical products?

The Supreme Court in the famous case of Cadila Health Care Ltd. v. Cadila Pharmaceuticals Ltd.[7], has held that a lesser degree of proof showing deceptive similarity must be used in trademarks in respect of medicinal products. Confusion in case of non-medical products may cause only economic loss but between medical products can cause loss of life. The Court has that a stricter approach is necessary and that there should be many clear indicators to distinguish two medicinal products from each other. The Delhi High Court has even accepted deceptive similarity between trademarks relating medicinal products, even if they were contained different ingredients[8].

Epilogue

The Court ultimately confirmed the ad-interim ex-parte order of injunction and dismissed the Defendant’s application under Order 39 Rule 4. The Plaintiff was saddled with costs of Rs. 10 Lakhs. From an understanding of the judgment, it is clear that even if medicines are used for different purposes, a strict approach needs to be taken to determine deceptive similarity.

[1]CS(COMM)-328/2022

[2] Madhavji Jeyram Kotak v. Jay Laxmi Gopalji Surji, 2007 SCC OnLine Bom 364

[3] Harkirat Singh v. Amrinder Singh, (2005) 13 SCC 511

[4] General Manager, Haryana Roadways v. Jai Bhagwan, (2008) 4 SCC 127; Phooltas Harsco Rail Solutions Private Limited v. Auto Components Private Limited, 2016 SCC OnLine Cal 202

[5] Dover Park Builders Pvt. Ltd. v. Madhuri Jalan, 2002 SCC OnLine Cal 413

[6] Corn Products Refining Co. v. Shangrila Food Products Ltd., (1960) 1 SCR 968

[7] (2001) 5 SCC 73

[8] Novartis AG v. Crest Pharma (P) Ltd., 2009 SCC OnLine Del 4390

Form 27 – Understanding Form 27 for Patentees and Licensees in the Post-2024 Amendment

Patents grant inventors exclusive rights over their creations for a…

Interpretation of Section 3(i) of the Indian Patent Act, 1970 in the Context of Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing

Introduction The advent of Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) has revolutionized…

Patent Publications vs Scientific Journal Publications: Understanding the Key Differences

Patent publications and scientific journal publications are two…

Categories

Recent Discussions

Form 27 – Understanding Form 27 for Patentees and Licensees in the Post-2024 Amendment

Patents grant inventors exclusive rights over their creations for a specific period. In India, patentees and licensees have a responsibility to disclose how…

Recent Discussions

Interpretation of Section 3(i) of the Indian Patent Act, 1970 in the Context of Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing

Introduction The advent of Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) has revolutionized prenatal diagnostics, enabling expectant parents to assess the genetic health of the fetus…